(A shorter version of this economic note was published in Business Day on 2 July 2025.)

South African (SA) exporters to the United States of America (USA) are facing an impending crisis with the 90-day suspension of President Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’ reciprocal tariffs scheduled to lapse on the 9th of July 2025. The immediate concern is the increase in tariffs from the current ‘universal’ baseline tariff of 10% to a SA-specific reciprocal tariff of 30%. These tariffs are in addition to the Section 232 tariffs on steel & aluminium (50%) and automobiles (25%) that President Trump imposed for national security reasons this year.

For South Africa, the US is a key export partner, accounting for 8.5% of non-gold exports in 2024. Gold is excluded as it is not reported in SA bilateral trade statistics and enters duty free into the US. Additionally, a third of SA non-gold exports to the US entered under AGOA preferences last year. However, AGOA preferences offer little cushion against the current tariffs. For example, South Africa’s top US-bound product, passenger vehicles, enjoyed a 2.5% tariff preference under AGOA, which is largely rendered meaningless by the 25% Section 232 tariffs on automobile imports. Similarly, the prospective 30% reciprocal tariff swamps the savings of 1.9 US cent per kilogram enjoyed by exporters of citrus products to the US under AGOA.

To assess the implications of the US tariffs on imports from SA, we develop a highly disaggregated multi-country, product-level trade and tariff model drawing on US reported import data for 2024. This model accounts for all new tariffs imposed on SA and other countries in 2025, as well as products exempted from the reciprocal tariffs (e.g. platinum group metals, selected wood products, ferro-alloys, copper, manganese and selected electronic goods). This model allows us to simulate the impact of the tariff increases on US imports from SA.

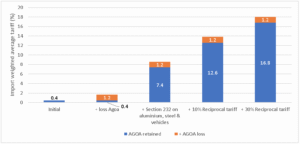

Our analysis shows that SA is particularly vulnerable to the lapsing of the 90-day suspension of reciprocal tariffs. At the current 10% reciprocal tariff rate, SA ranks 102nd out of 221 countries in terms of the severity of tariff increases on US imports. However, SA’s ranking would fall to 28th out of 221 countries should the suspension lapse without any other agreement replacing it. Overall, the increase in reciprocal tariffs to 30% would significantly increase SA’s weighted average tariff on exports to the USA from 0.4% prior to any of the tariff increases to 16.8% (Figure 1). While products exempted from the tariff increases comprise a large share of SA export value to the US, these products are few in number. Over 80% of all products exported face the full brunt of the 30% reciprocal tariff increase. Further, if AGOA is not renewed in September this year, SA’s weighted average tariffs will increase by an additional 1.2 percentage points.

Figure 1: Import weighted tariffs on US non-gold imports from SA under different tariff increases, with and without AGOA access.

Using the simulation model, we find that the negative trade effects under the current 10% reciprocal tariffs and the Section 232 tariffs amount to $1 billion or a 12.4% decline in SA non-gold exports to the US. This has the potential to rise to $2.3 billion or a 28% decline in non-gold exports to the US once the suspension lapses on the 9th of July. The effects are widely felt across products. The median product, for example, experiences a 45% reduction in US imports from SA, but some products experience a complete collapse in US imports. While the impact on US imports from SA is large, the impact on total non-gold exports by South Africa to the world is much lower at 2.2%, given that the US only accounts for a fraction of total SA exports.

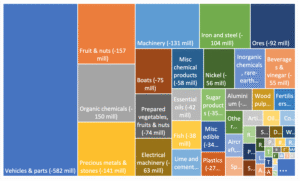

In terms of value, US imports of vehicles and parts is the most severely affected, falling by $582 million, or a 32% decline (Figure 2). This decline, however, is not attributed to the 30% reciprocal tariff, which does not apply to vehicles, but rather to the 25% Section 232 tariffs, which are not expected to change on the 9th of July. Industries facing greater proportionate losses from the 30% reciprocal tariffs are, amongst others, organic chemicals ($150 million, 74%), fruit & nuts ($157 million, 65%), prepared vegetables ($74 million, 68%) and sugar products ($35 million, 92%).

The negative impact of the 30% reciprocal tariff on SA is amplified by the potential diversion of US consumers away from SA products towards alternatives exported by other countries that face lower US tariff increases. These diversion effects are most severely felt in chemicals and food products, and account for over 80% of the total decline in US imports from SA. Citrus, a key SA export product to the USA, is also at serious risk of diversion given that competing Southern Hemisphere exporters in Chile and Peru will face a much lower 10% reciprocal tariffs from the 9th of July. There are also positive diversion effects for SA from China ($56 million to $123 million) in face of the 20% fentanyl tariffs and China’s relatively higher 34% reciprocal tariff. However, these are limited due to SA’s high severity rank in terms of reciprocal tariffs.

Figure 2: Product composition of the decline in US non-gold imports from SA following tariff increases (total decline equals $2.3 billion)

Authors’ calculations using trade and tariff data sourced from the US International Trade Centre and SA Revenue Services, and tariff changes from the US Federal Register.

Not all products are directly affected by the US tariffs. US imports, for example, of platinum, copper, mineral fuels and pharmaceuticals are unaffected as tariffs do not change on these products. However, this may change soon as Section 232 investigations have been initiated to assess whether imports of copper, timber, trucks, critical minerals and pharmaceuticals threaten to impair national security. Further, should US or global growth slow in response to the increased tariffs, foreign demand and international prices may fall, resulting in large additional negative indirect effects for SA exporters of all products.

An additional consideration for SA exporters, is the potential increase in competition in markets outside of the US, in particular from China. China has been one of the most severely targeted countries by Trump’s foreign policies to date, with reciprocal tariffs at one point rising to 145%. If Chinese exports are deflected away from the US to other markets, as occurred during the 2018/19 US-China trade war, then SA exporters may find themselves crowded out of these markets. Anecdotal evidence of this has already surfaced with reports of rising Chinese exports to Africa, Southeast Asia and Europe surging in recent months. We assess this risk for SA in its major regional market for manufactured goods, namely Sub-Saharan Africa. Using a common market share analysis, we find that the indirect deflection effects constitute a relatively low risk for SA. Displaced exports in Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries amount to a decline of less than 1% of SA’s regional exports. The structure of South Africa’s exports to the region appears to be resilient, suggesting that preferential trade agreements within the region may play a role.

In light of our results, it is imperative that SA adopt a coordinated policy response. The immediate concern is the impending increase in reciprocal tariffs on the 9th of July. If no deal can be struck, South Africa risks losing a significant amount in exports to the US, which will be amplified if other competing countries are successful in negotiating lower tariff increases. Beyond that, priorities should extend to the renewal of AGOA beyond 2025. A renewal of AGOA that exempts SA and other SSA imports from some or all of the newly introduced tariffs would ensure that the original ‘spirit’ of AGOA is restored. Longer term, SA also needs to prioritise enhancing domestic trade competitiveness and diversifying its export destinations. In this regard, pursuing continental-level agreements such as the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) with more impetus and other forms of preferential trade agreements are important avenues to explore.

The crisis has highlighted the imperative of better engagement between private companies and government. According to the American Chamber of Commerce in South Africa Business Barometer (2021), there are at least 662 American firms active in the country, that not only support 220,000 local jobs, but also benefit their US shareholders/owners, as reflected in the large net positive primary income transfers from SA to the US. Re-invigorating the dormant SA-US Trade and Investment Agreement (TIFA) as a bilateral forum for public and private sector dialogue and cooperation on trade and investment facilitation between the two countries, is crucial.

Opportunities for deeper reform also arise in the face of the tariff threats. The US National Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Trade Barriers by the Office of the US Trade Representative highlights several impediments to trade, including restrictive non-tariff barriers and import permit requirements, technical and phytosanitary barriers covering certification, domestic lab testing requirements, local ownership requirements on foreign investment, and limits to competition by government procurement. Now is the opportunity to re-evaluate these policies and assess whether they are consistent with driving growth and SA’s integration in the global market. Further, trade costs remain very high in SA, in large part because of the very poor quality and administration of rail and port infrastructure. High trade costs prevent the entry of firms into export markets, and make SA exports particularly vulnerable to external shocks. The US tariff increases accentuate the importance of accelerating and expanding the existing reforms of the state institutions managing critical trade infrastructure.